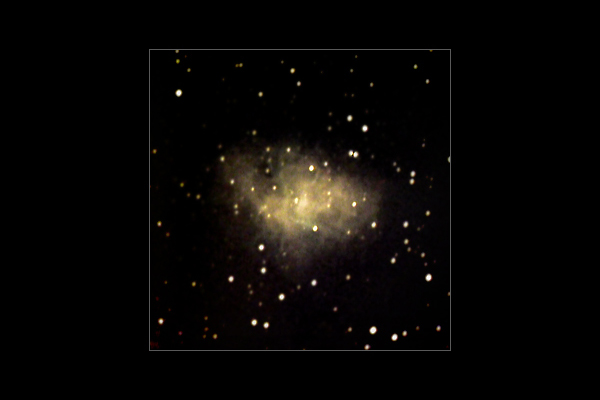

On a summer day in A.D. 1054, Chinese astronomers looked up at the sky and saw a new star. At first, it was brighter than the planet Venus and visible even in daylight, but month after month the “guest star” dimmed until it finally faded beyond their power to see. Almost a thousand years later I captured the image that you see above. Now known as the Crab Nebula, it is all that remains of the brilliant explosion that the Chinese astronomers saw, visible to me now only by using a telescope, a digital camera, and a personal computer.

Telescopes routinely reveal the invisible. Every night, visions of every marvel in the universe pour down on our heads. Some, like the Moon, are visible to our unaided eyes and seeing them inspire songs and poems. Others, are too faint for our feeble senses and remain unseen and unappreciated. A telescope captures the light raining down from the universe and concentrates it into a bright image that the eye can appreciate. Telescopes reveal the beauty that we otherwise cannot see.

A camera connected to a telescope can see even more. Both film and digital cameras are more sensitive than the human eye, especially if the film or sensor is allowed to accumulate light for a long period of time. Even the faintest light leaves a trace.

But the most fascinating component of my imaging setup is probably the personal computer. This may be counter-intuitive at first. After all, the telescope is capturing the light and the camera is recording it. All the computer can do is re-arrange the data that it is given. It can’t really add any extra information, can it? How can it be that important?

On the night that I took the picture of the Crab Nebula, the skies over Cambridge, Massachusetts were clear but brightened by the usual light-pollution of an urban center. When I looked at the Crab Nebula through my telescope I saw nothing—exactly what Chinese astronomers saw after their guest star disappeared. I hooked up a CCD camera (a kind of digital camera) to the telescope and recorded the nebula’s light for 30 minutes. The resulting image (which you can see below) was no more than a smudge. It was not until after I processed the image on the computer that I was able to obtain the final image. All of the detail, subtlety, and (dare I say it?) beauty in the final picture was brought out by the computer. All of it was there in the raw image, but it remained invisible until the computer could reveal it. Computers too can reveal beauty.